library(tidyverse)

library(vdemlite)

library(broom)

library(purrr)

# Load V-Dem data for 2019

model_data <- fetchdem(

indicators = c("v2x_libdem","e_gdppc","v2cacamps"),

start_year = 2019, end_year = 2019

) |>

rename(

country = country_name,

lib_dem = v2x_libdem,

wealth = e_gdppc,

polarization = v2cacamps

) |>

filter(!is.na(lib_dem), !is.na(wealth))Least Squares Regression

November 6, 2025

Prework

Download shotput.csv from Blackboard resources.

Run this once to load packages and data for today:

Models

Last time: Fitting Data to a Line

- Defined models and tasks (regression vs. classification)

- Explored correlation and visualized \(X \leftrightarrow Y\)

- Fit a simple line, read slope/intercept, checked residuals and \(R^2\)

Today:

- Understand regression as an optimization framework: how R chooses the “best” line

- Visualize the cost function and why we minimize squared errors

- Explore when a linear model is not enough, introducing nonlinear regression

- Understand regression as an optimization framework: how R chooses the “best” line

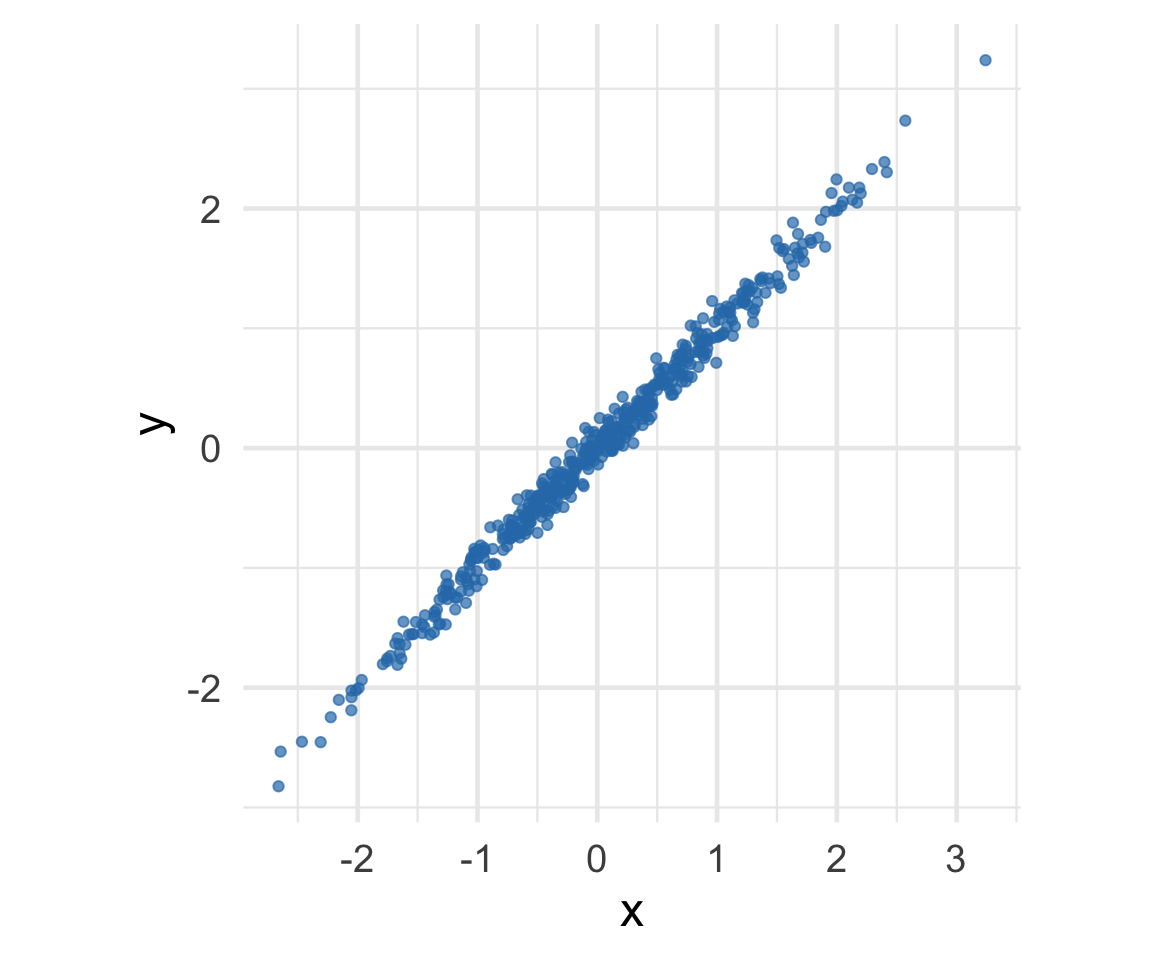

Where is the prediction line? Example 1

[1] "r = 0.99"

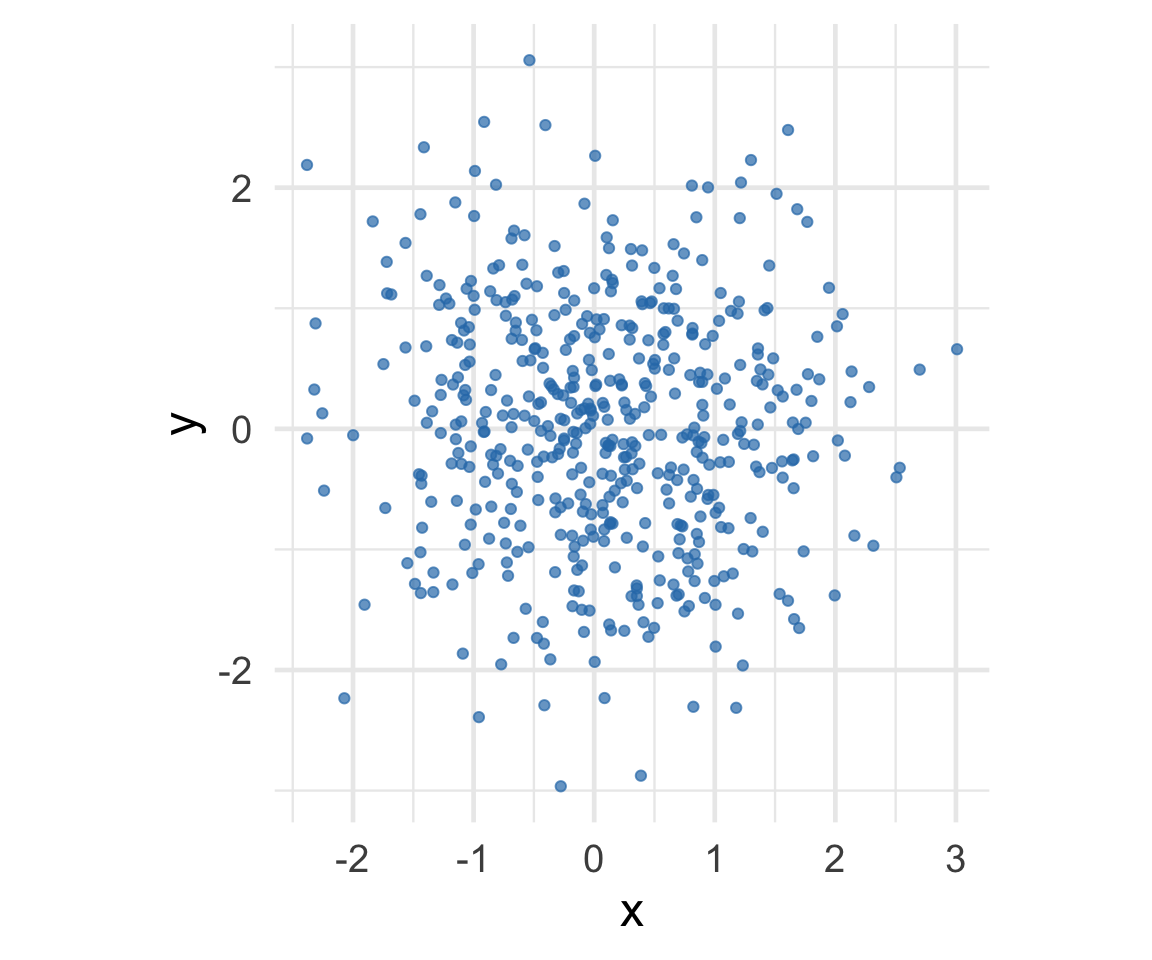

Where is the prediction line? Example 2

[1] "r = -0.06"

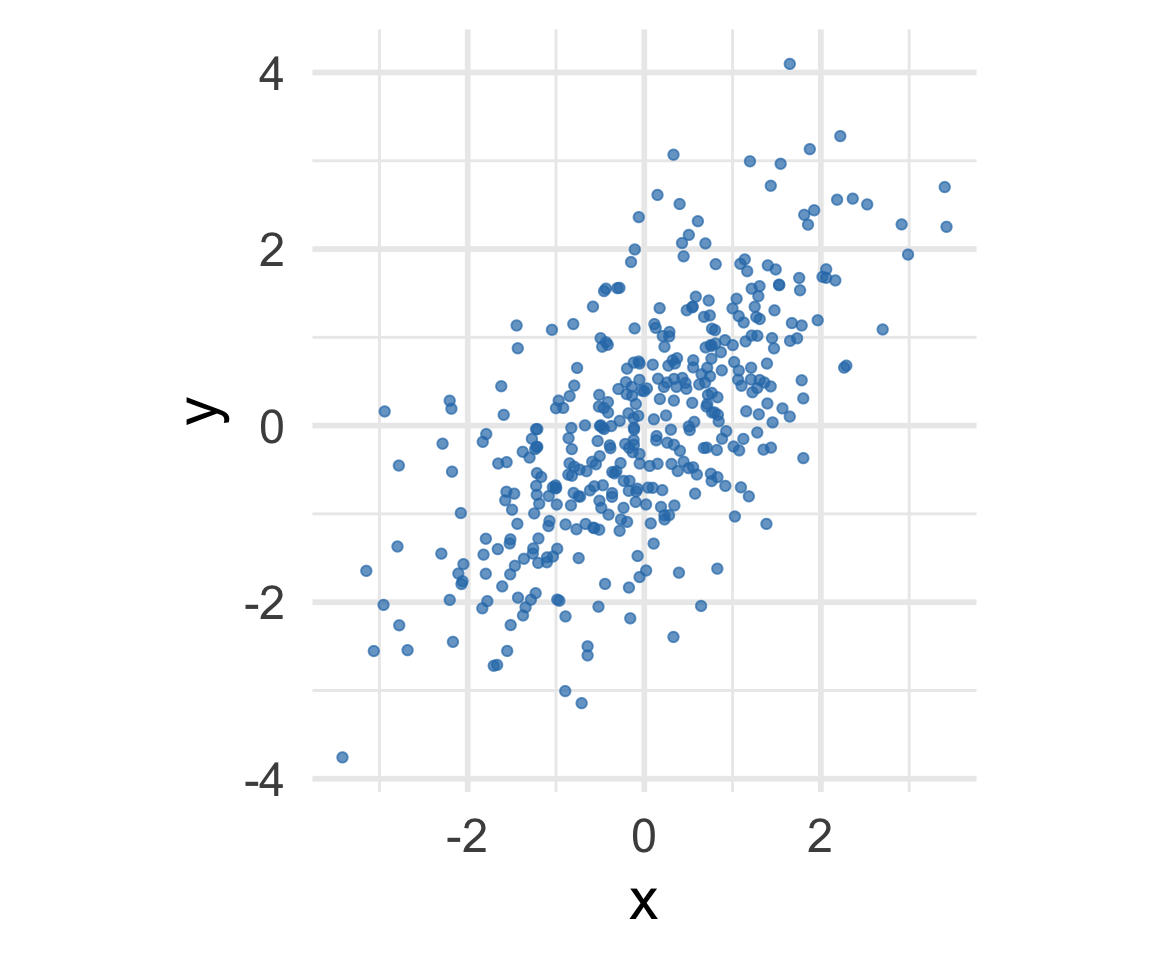

Where is the prediction line? Example 3

[1] "r = 0.66"

Linear Regression Model

- A model is a simplified mathematical description of a relationship.

\[\widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x\]

- \((b_1)\): change in \(( \widehat{y} )\) for a 1‑unit change in \((x)\)

- \((b_0)\): predicted value when \((x=0)\)

A simple one-dimensional linear model.

From Correlation to Regression

Correlation tells us how tightly \(x\) and \(y\) move together.

Regression uses that same idea to draw the best-fitting line.

In standardized (SD) units, the regression line can be written as:

\[ SD(\widehat{y}) = r \times SD(x) \] or \[ \frac{\widehat{y} - \bar{y}}{s_{y}} \;=\; r \times \frac{x - \bar{x}}{s_x} \]

where \(s\) is standard deviation.

From Correlation to Regression

Since \(s_{\widehat{y}} = |r|s_y\), the predicted values vary less than the actual data when \(|r|<1\).

We can re-arranged into the form \[ \widehat{y} = (\text{slope}) \times x + (\text{intercept}) \]

Correlation and the Regression Line

- The slope depends on both \(r\) and the scales of \(x\) and \(y\):

\[ b_1 = r \times \frac{s_y}{s_x} \] - The intercept anchors the line at the means:

\[ b_0 = \bar{y} - b_1 \bar{x} \]

Your turn!

A course has a midterm (average 70; standard deviation 10) and a really hard final (average 50; standard deviation 12)

If the scatter diagram comparing midterm & final scores for students has an oval shape with correlation 0.75, then…

What do you expect the average final score would be for students who scored 90 on the midterm?

How about 60 on the midterm?

05:00

Your Turn: Predicting from Correlation

Given:

- Midterm (X):

- Mean \(\bar{x} = 70\)

- Standard deviation \(s_x = 10\)

- Mean \(\bar{x} = 70\)

- Final (Y):

- Mean \(\bar{y} = 50\)

- Standard deviation \(s_y = 12\)

- Mean \(\bar{y} = 50\)

- Correlation: \(r = 0.75\)

Your Turn: Predicting from Correlation

Step 1: Compute the Slope

\[ b_1 = r \times \frac{s_y}{s_x} = 0.75 \times \frac{12}{10} = 0.9 \]

Your Turn: Predicting from Correlation

Step 2: Compute the Intercept

\[ b_0 = \bar{y} - b_1 \bar{x} = 50 - (0.9)(70) = 50 - 63 = -13 \]

Your Turn: Predicting from Correlation

Step 3: Regression Line

\[ \widehat{y} = -13 + 0.9x \]

Your Turn: Predicting from Correlation

Step 4: Make Predictions

For a student who scored 90 on the midterm:

\[ \widehat{y} = -13 + 0.9(90) = 68 \]

Expected final score: 68

For a student who scored 60 on the midterm:

\[ \widehat{y} = -13 + 0.9(60) = 41 \]

Expected final score: 41

Today: Least-squares optimization

- Understand regression as an optimization framework—how R chooses the “best” line

- Visualize the cost function and why we minimize squared errors

- Explore when a linear model is not enough, introducing nonlinear regression

The least-squares method can be used for solving for coefficients for both linear or nonlinear models.

Which line is best?

Optimization Idea (Why “Least Squares”?)

For any line \(\widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x\), define the residuals

\(y_i - \widehat{y}_i\).

The cost (objective) we minimize is the sum of squared residuals (SSR):

\[ SSR = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \widehat{y}_i)^2 \]

Minimizing SSR (or the equivalent MSE = SSR / \(n\)) picks the “best” line among all possibilities.

Tiny Three-Point Example

Three points: \((1,1), (2,2), (3,3)\). Try different slopes with intercept fixed at 0 and compute SSR.

#| '!! shinylive warning !!': |

#| shinylive does not work in self-contained HTML documents.

#| Please set `embed-resources: false` in your metadata.

#| standalone: true

#| viewerHeight: 500

#| echo: false

library(shiny)

data_points <- data.frame(x = c(1, 2, 3), y = c(1, 2, 3))

ui <- fluidPage(

titlePanel("Interactive Cost Function Explorer"),

sidebarLayout(

sidebarPanel(

sliderInput("slope",

"Slope Parameter:",

min = -2, max = 4, value = 1, step = 0.1),

br(),

h4("Current Values:"),

textOutput("current_slope"),

textOutput("current_equation"),

textOutput("current_ssr"),

br(),

p("Move the slider to see how the slope affects:"),

tags$ul(

tags$li("The regression line (left plot)"),

tags$li("Your position on the cost function (right plot)")

)

),

mainPanel(

plotOutput("combined_plot", height = "400px")

)

)

)

server <- function(input, output) {

# Fixed: Calculate predictions and residuals properly

current_calculations <- reactive({

predictions <- input$slope * data_points$x

residuals <- data_points$y - predictions

ssr <- sum(residuals^2)

list(predictions = predictions, residuals = residuals, ssr = ssr)

})

cost_data <- reactive({

slopes <- seq(-2, 4, by = 0.1)

ssr_values <- sapply(slopes, function(b) {

preds <- b * data_points$x

resids <- data_points$y - preds

sum(resids^2)

})

list(slopes = slopes, ssr = ssr_values)

})

output$current_slope <- renderText({

paste("Slope:", round(input$slope, 2))

})

output$current_equation <- renderText({

paste0("Equation: Ŷ = 0 + ", round(input$slope, 2), " * X")

})

# Fixed: Use the corrected reactive calculations

output$current_ssr <- renderText({

calc <- current_calculations()

ssr_terms <- paste0("(", data_points$y, " - ", round(calc$predictions, 2), ")^2", collapse = " + ")

ssr_value <- round(calc$ssr, 2)

paste0("SSR: ", ssr_terms, " = ", ssr_value)

})

output$combined_plot <- renderPlot({

par(mfrow = c(1, 2), mar = c(4, 4, 2, 1))

# Left: Regression plot

plot(data_points$x, data_points$y, pch = 19, col = "blue",

xlim = c(0, 4), ylim = c(-2, 6),

xlab = "x", ylab = "y", main = "Regression Line")

abline(0, input$slope, col = "red", lwd = 2)

# Add residual lines for visualization

calc <- current_calculations()

segments(data_points$x, data_points$y, data_points$x, calc$predictions,

col = "gray", lty = 2)

# Right: Cost function

cost <- cost_data()

plot(cost$slopes, cost$ssr, type = "l", col = "darkred", lwd = 2,

xlab = "Slope Parameter", ylab = "Sum of Squared Residuals",

main = "Cost Function")

points(input$slope, calc$ssr, col = "red", pch = 19, cex = 1.5)

})

}

shinyApp(ui = ui, server = server)simple_data <- tibble(x = c(1,2,3), y = c(1,2,3))

ssr_for_slope <- function(b1){

preds <- b1*simple_data$x

sum((simple_data$y - preds)^2)

}

tibble(slope = seq(-2,4,by=.5)) |>

mutate(ssr = map_dbl(slope, ssr_for_slope))# A tibble: 13 × 2

slope ssr

<dbl> <dbl>

1 -2 126

2 -1.5 87.5

3 -1 56

4 -0.5 31.5

5 0 14

6 0.5 3.5

7 1 0

8 1.5 3.5

9 2 14

10 2.5 31.5

11 3 56

12 3.5 87.5

13 4 126 Minimum is at slope = 1 (SSR = 0). The cost curve is a parabola.

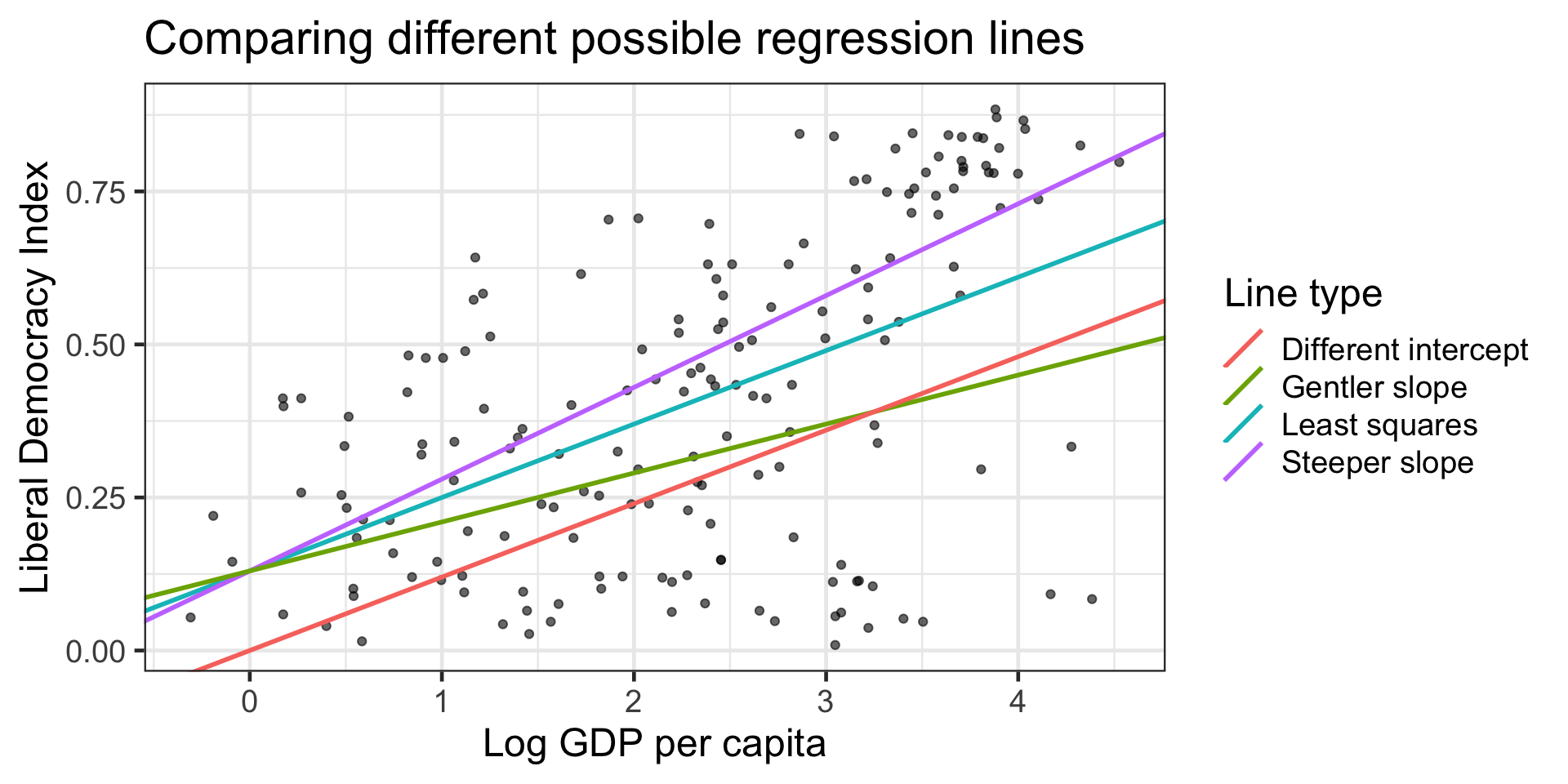

Worked Example: Democracy and GDP

First, let’s have R find the least squares line:

# Fit the model

democracy_model <- lm(lib_dem ~ log(wealth), data = model_data)

# Show the summary

names(democracy_model) [1] "coefficients" "residuals" "effects" "rank"

[5] "fitted.values" "assign" "qr" "df.residual"

[9] "xlevels" "call" "terms" "model" (Intercept) log(wealth)

0.1305119 0.1204045 The least squares solution is approximately: \(\widehat{Democracy} = 0.13 + 0.12 \times \log(GDP)\)

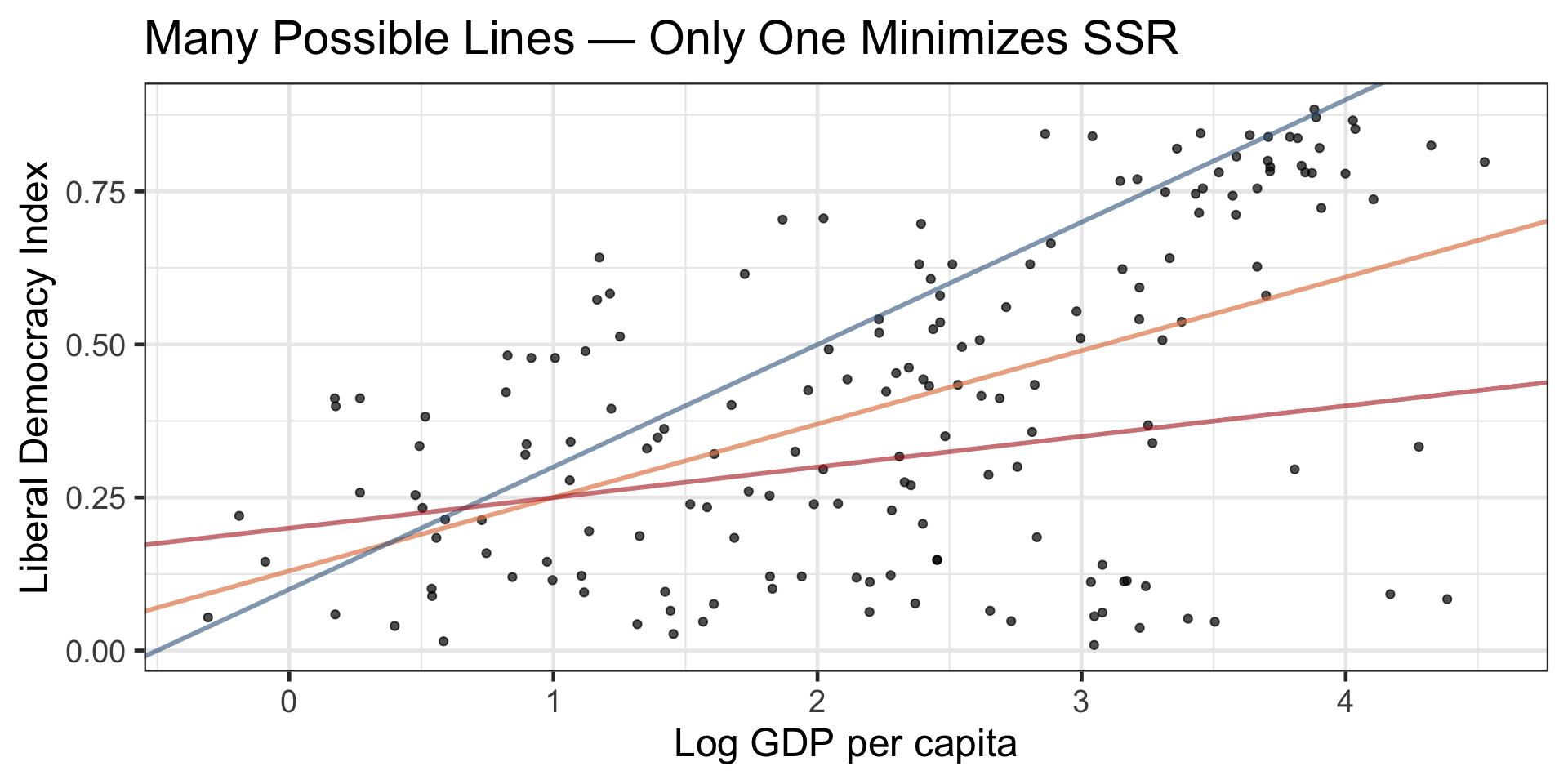

Worked Example: Democracy and GDP

Let’s compare several candidate lines on the V‑Dem data and compute their SSR.

Code

# Different lines parameters

test_lines <- tibble(

intercept = c(0.13, 0.13, 0.13, 0.00),

slope = c(0.12, 0.15, 0.08, 0.12),

description = c("Least squares", "Steeper slope", "Gentler slope", "Different intercept")

)

# Visualize

ggplot(model_data, aes(x = log(wealth), y = lib_dem)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6) +

geom_abline(aes(intercept = intercept, slope = slope, color = description),

data = test_lines, size = 1) +

labs(x = "Log GDP per capita", y = "Liberal Democracy Index",

title = "Comparing different possible regression lines",

color = "Line type") +

theme_bw(base_size = 18)

Least squares line (intercept = 0.13, slope = 0.12): SSR = 8.57

Steeper slope line (intercept = 0.13, slope = 0.15): SSR = 9.58

Gentler slope line (intercept = 0.13, slope = 0.08): SSR = 10.49

Different intercept line (intercept = 0.00, slope = 0.12): SSR = 11.58

What lm() Is Doing

lm(lib_dem ~ log(wealth), data = model_data) returns the coefficients that minimize SSR.

# A tibble: 2 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 0.131 0.0381 3.43 7.58e- 4

2 log(wealth) 0.120 0.0147 8.19 5.75e-14actual_ssr <- sum(residuals(democracy_model)^2)

cat("SSR of least-squares line:", round(actual_ssr, 3), "\n")SSR of least-squares line: 8.574 You can think of lm() as solving the calculus for you (there’s a closed-form solution for simple linear regression).

From Linear to Nonlinear Models

We started with a linear model: a straight line that relates \(x\) and \(y\):

\[ \widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x \]

But what if the relationship bends or curves?

Extending the Model Form

We can still use regression, but with an alternative nonlinear model that allows for powers of \(x\):

| Model Type | Equation | Shape |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | \(\widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x\) | Straight line |

| Quadratic | \(\widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x + b_2 x^2\) | Gentle curve (U- or ∩-shaped) |

| Cubic | \(\widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 x + b_2 x^2 + b_3 x^3\) | S-shaped or inflected |

Nonlinear least squares

- We’re still using least squares—minimizing the same squared errors.

- What changes is the shape of the function or model we fit to the data.

- Linear in the parameters (\(b_0, b_1, b_2, \dots\))

We can still a linear regression model, even if the curve isn’t straight.

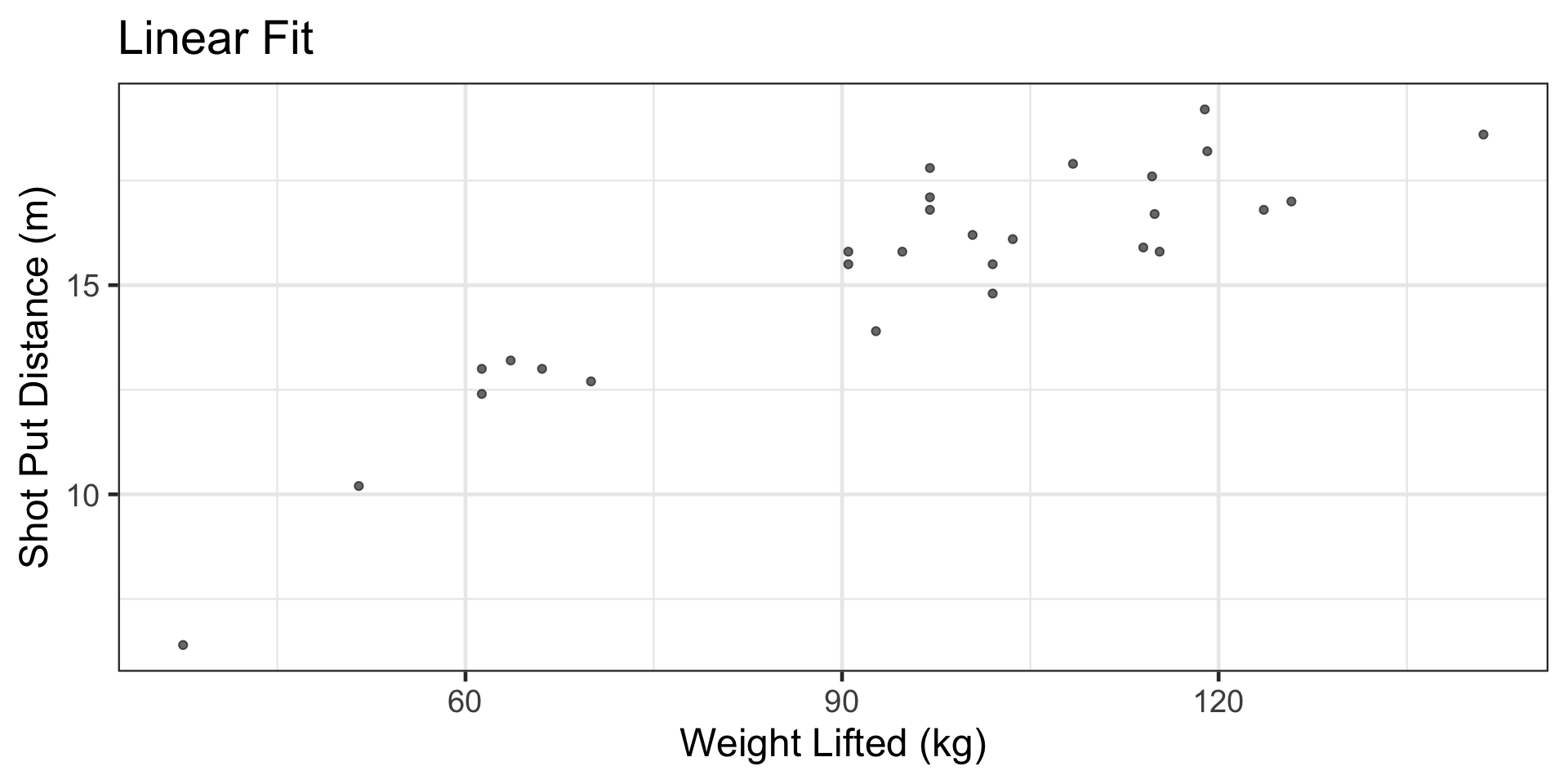

Example: Shotput — Linear vs. Nonlinear

Here’s some shotput data with variables for strength and distance.

Example: Shotput

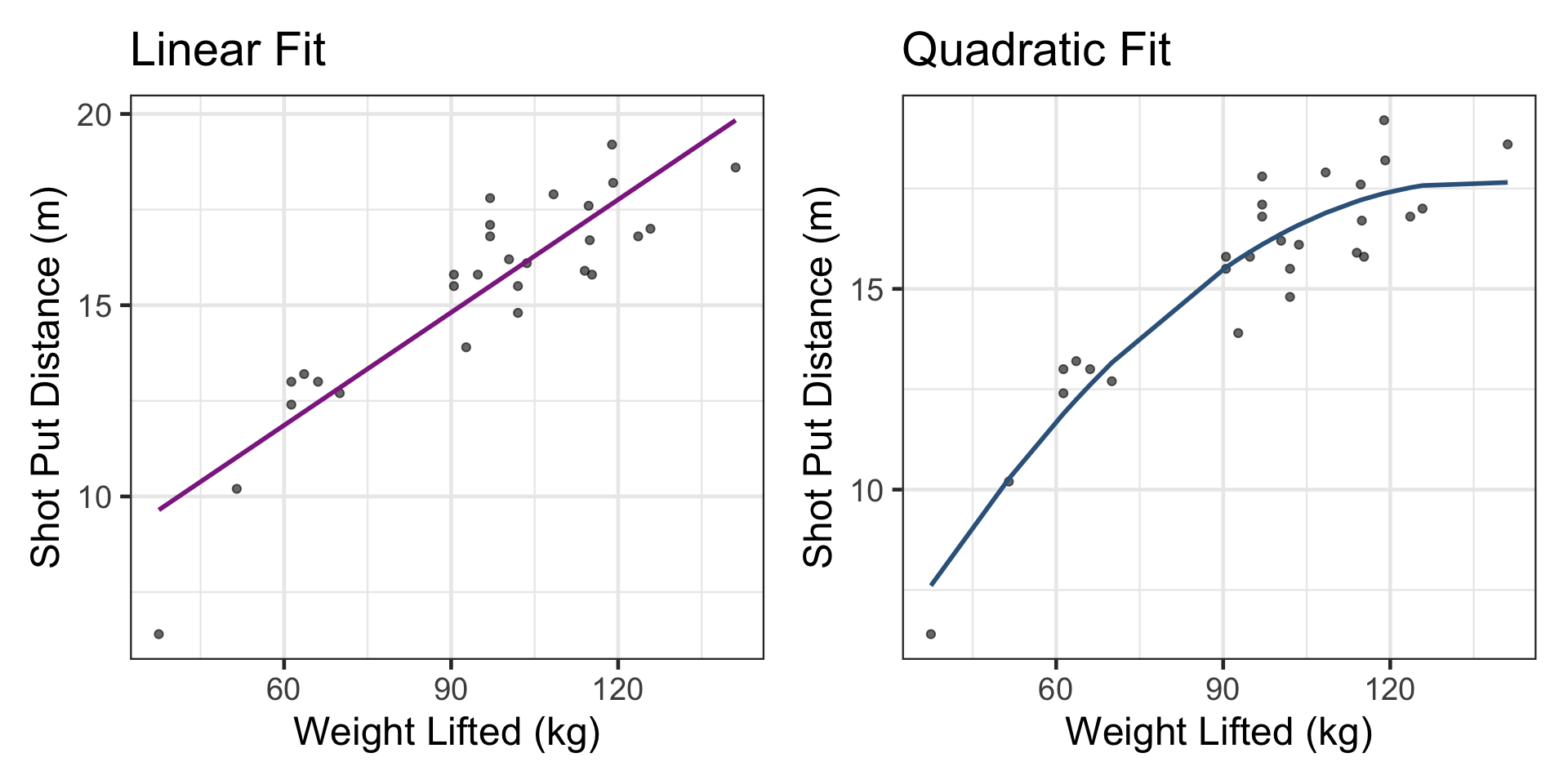

Example: Shotput

This study postulated a quadratic relation between the weight lifted and the shot put distance.

Add the polynomial term to the model

Example: Shotput

Compare linear vs. nonlinear fit visually

Code

p1 <- ggplot(shotput, aes(x = `Weight Lifted`, y = `Shot Put Distance`)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6) +

geom_line(data = aug_lin, aes(y = .fitted), color = "#8E2C90", linewidth = 1) +

labs(

title = "Linear Fit",

x = "Weight Lifted (kg)",

y = "Shot Put Distance (m)"

) +

theme_bw(base_size = 18)

p2 <- ggplot(shotput, aes(x = `Weight Lifted`, y = `Shot Put Distance`)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6) +

geom_line(data = aug_quad, aes(y = .fitted), color = "steelblue4", linewidth = 1) +

labs(

title = "Quadratic Fit",

x = "Weight Lifted (kg)",

y = "Shot Put Distance (m)"

) +

theme_bw(base_size = 18)

library(patchwork)

p1 + p2

Example: Shotput

Which has smaller SSR?

SSR_linear SSR_quadratic

41.63726 26.99472 Least squares still minimizes SSR, but if the model form is wrong (line for a curved relation), the minimized SSR can still be large. Choose features / terms that reflect the pattern.

Try it out!

- Replace

Weight Liftedwith a log transform withlog()or standardize it withscale, refit both models, and compare SSR.

- Try cubic by adding

I(strength^3). Does adj.\(R^2\) improve meaningfully?

Try it out!

Try it out!

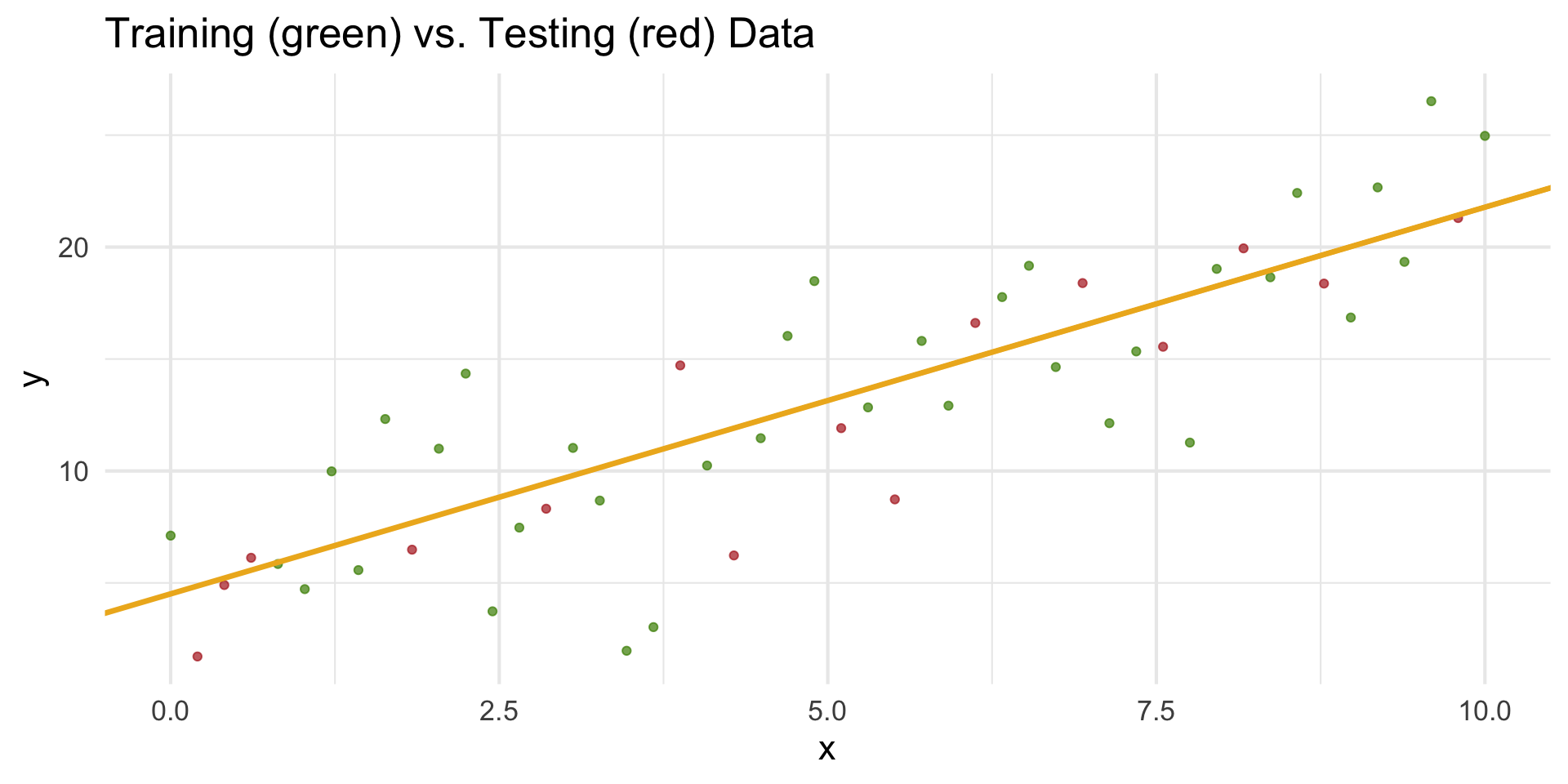

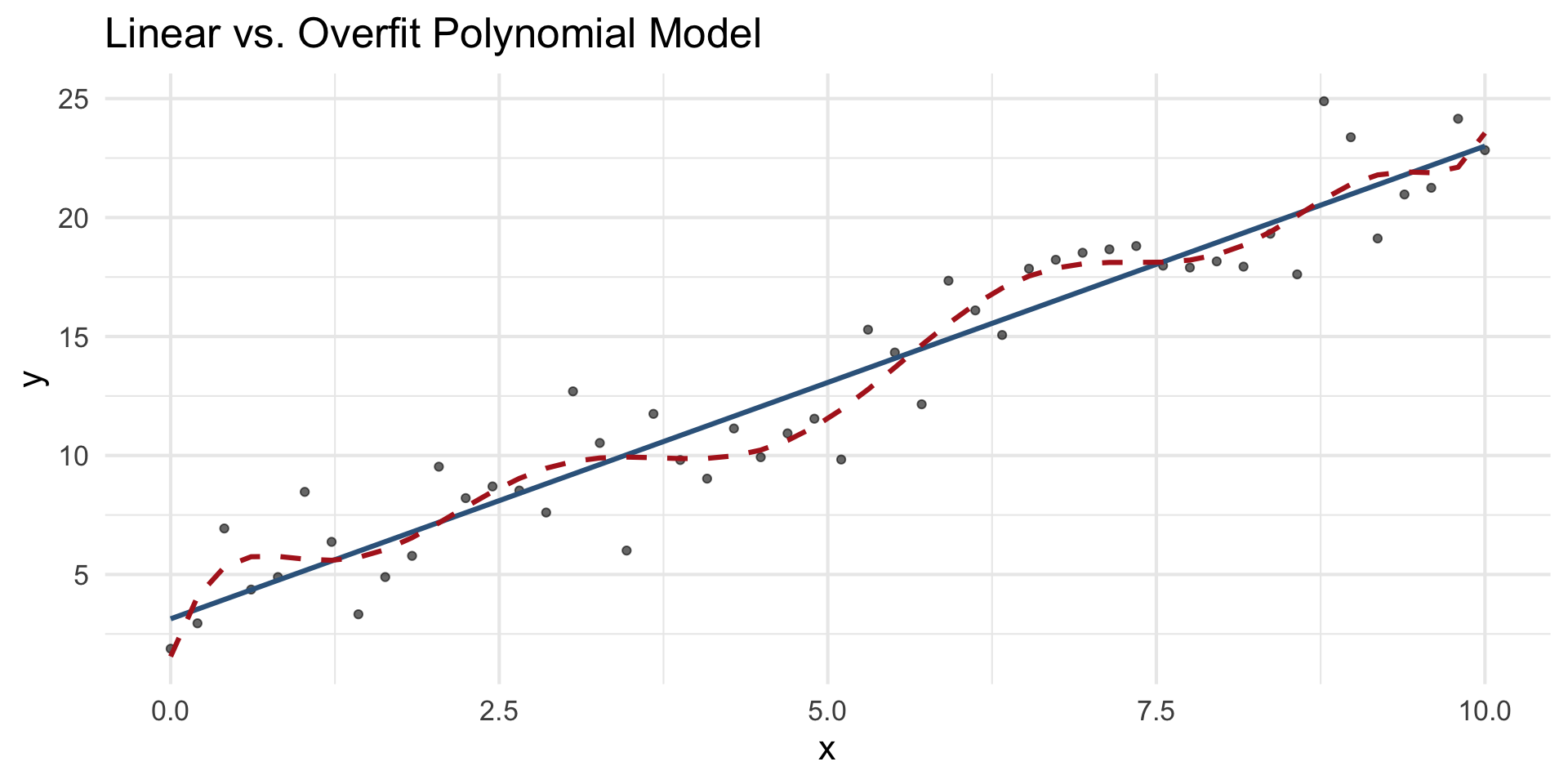

Beyond Fit: Training vs. Testing Data

- A model that fits the training data extremely well may not perform well on new data.

- Training data: used to estimate the model parameters (fit).

- Testing data: used to evaluate how well the model generalizes.

Overfitting vs. Underfitting

Model Validation trends

- Training error always decreases with model complexity.

- Test error eventually increases — a sign of overfitting.

- Always check generalization using test data, cross-validation, or resampling.

- The goal isn’t the lowest SSR on training data — it’s the lowest error on unseen data.

When least square methods doesn’t work

When the model is nonlinear in the parameters,

there’s no algebraic way to solve for the \(b\)’s.

Example models:

\[ \widehat{y} = b_0 + b_1 e^{b_2 x} \quad \text{or} \quad \widehat{y} = \frac{b_0}{1 + e^{-b_1(x - b_2)}} \]

Here, \(b_2\) appears inside an exponential or denominator.

So we use numerical optimization instead.

Summary

- Least squares chooses \((b_0,b_1)\) to minimize SSR. That’s what

lm()computes.

- Visualizing candidate lines + SSR builds intuition for the optimization.

- Good optimization can’t rescue a bad model form. Inspect shapes, consider transforms or polynomial terms.